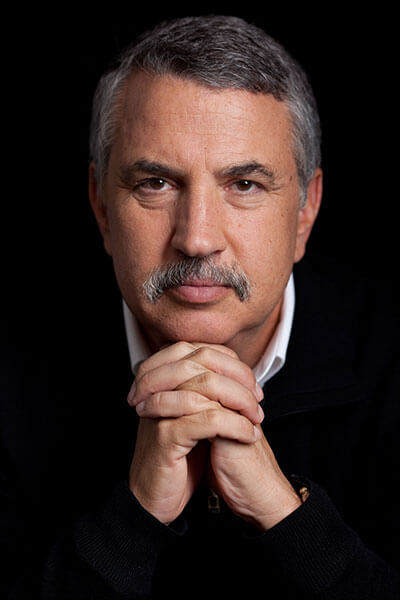

Author and The New York Times foreign affairs columnist Thomas Friedman will speak at Convening Leaders 2021 in January. (Courtesy of ICM Speakers)

For more than two decades, author and The New York Times foreign affairs columnist Thomas Friedman has been writing about the intertwined effects of globalization, technology, and environmental degradation — all three of which have been accelerating dramatically.

The story of how COVID-19 emerged as a global pandemic illustrates the very points he has been making — “you can see the whole thing there,” said Friedman, a three-time Pulitzer Prize winner and the author of Hot, Flat, and Crowded, and six more books.

Friedman, a Main Stage speaker at PCMA Convening Leaders 2021, spoke to Convene by telephone.

You speak and write about the pace of change and the exponential growth in areas including globalization, technology, and climate change. Could you talk a little bit about how the pandemic has interacted with those things?

Well, the pandemic reflects my thesis in several ways. The first is that the thing that would actually trigger both the first SARS outbreak in 2002 and then this one is accelerating growth, particularly of urban areas. Basically, what happened was that as these urban areas expanded into wilderness areas, they killed the [predators at the top of the food chain] in these wilderness areas, and left behind only generalized species of bats, rats, and primates that can live in degraded ecosystems. And these generalized species evolved in the wild with these coronaviruses.

Then the virus that jumped from the wilderness outside of Wuhan into Wuhan was quickly able to jump from Wuhan into the world, because there were now 3,200 flights a year from China to the United States. In fact, there were 50 direct flights from Wuhan to the United States.

In a year that has forced us to pay attention, do you see a change toward people connecting the dots a little bit more?

They should be if they’re paying attention. Right now, people are just so focused on surviving the pandemic. But I hope as we come out of this, we will sit back and realize that we’ve been connecting the world, and connecting more global nodes, farther, faster, deeper, and cheaper, so that globalization is going wider. We’ve then accelerated the connections between those nodes, thanks to everything from telecommunications and air transport and sea transport.

Thomas Friedman is one of three keynote speakers at Convening Leaders 2021.

But we’ve also been taking out the buffers between those nodes, the surge protectors, things that prevent the flow of bad stuff from a single node infecting the whole system. So, when you break down the natural barriers between wilderness areas and urban areas, you’re actually taking out buffers. When you take out a financial regulation, you take out buffers. You end up with things like global financial pandemics. When you destroy mangroves and rainforests, you’re limiting buffers to climate change. When you take out the buffers between them, you can get some very disturbing effects, where a small disturbance in one part of the global system can now quickly be transmitted to the whole system.

You’ve also talked about what you’ve called the “infodemic” — the onslaught of unverified information.

Now we’ve lost the buffer of editors. Editors are buffers. Right when we needed edited science most, basically, we had created a world where one node could suddenly transmit a conspiracy theory to the whole system much more quickly without the buffer of editors.

The world that PCMA is in is education and business events. Where do you think that industry plays a role?

It’s all the more important. I work for an edited newspaper. I can’t just sit down on my platform and write whatever I want. In the kind of world that we’re talking about, that I just described, it’s a world where you really do need to have thoughtful editors and buffers against the wildest kinds of untruths and conspiracy theories.

And that’s true if you’re sponsoring a conference. And this is not a left/right question. It’s simply that you want people whose political opinions — left, right, or center — are grounded in science and facts and stress-tested a little bit and not just tossed out into the world willy-nilly. Because in this world where technology and globalization are accelerating so quickly, those crazy ideas can go farther, faster, deeper, and cheaper than ever before.

And then suddenly you’re trying to inoculate your population against, say, a virus, and you need herd immunity, which means you need 60 to 70 percent of the population [to have antibodies], but you wake up and discover that 50 percent of your population either doesn’t believe in the virus or doesn’t believe in vaccines. So it does matter what conference you’re holding. It does matter what speakers you’re putting out before your community.

“In the kind of world that we’re talking about, … you really do need to have thoughtful editors and buffers against the wildest kinds of untruths and conspiracy theories.” — Thomas Friedman

How has the experience of speaking digitally been different than being there in person? Have you talked to the same audiences and do you get the same sense of connection?

I’ve done groups as big as 250,000 in China, [and as small] as a dozen. And obviously it’s not like being there in person, but I feel like the technology has gotten better and I’ve gotten better, so that I can communicate my thoughts in ways that audiences still find compelling. It depends on the group and the size and frankly sometimes the technology. But when you get it right, it can feel about 80 percent as good as being there.

And frankly from a speaker’s point of view, it’s 100 percent less stress on my body. So, I’ve done webinars from Australia to India to China to all over the Middle East; I’ve taught classes. I’ve been able to actually do a lot more things. And again, they’re not like being there — I can’t roam around, look you in the eye, notice your arched eyebrows or your quizzical look so easily — but it’s about 80 percent as good.

So, I see these as increasingly being part of my future. I can imagine the future, frankly, from a speaker’s point of view, where I’d have one rate if you want me in person and one rate if you want me as a webinar.

When you spoke earlier this year to the Eisenhower Fellowships Annual Meeting, you called trust “the only legal performance-enhancing drug.” Could you talk about the future of trust?

Well, that was a quote from my teacher Dov Seidman. And trust really is the only legal performance-enhancing drug — people can go so fast when there’s trust in the room. Because trust is like a hard floor: You can dunk a basketball if you’re even a short person off a hard floor. The absence of trust is like the Syrian desert. You can’t jump a millimeter. And so it’s hard to build trust in a pandemic, but the non-authoritarian countries that are doing well are pretty high-trust societies — South Korea, for instance. When people trust each other, they can go very fast, very far. When they don’t trust each other, you really can’t go very far. … And look at Washington, D.C., right now and how hobbled we are.

Do you think there is a pent-up need for people to go and see each other?

I really do think there will be. I certainly feel it myself. I miss my friends. I miss my contacts. I miss going and smelling and feeling and touching and eating and tasting. So, all of those things, definitely.

Do you miss going to conferences?

I wouldn’t do it if I didn’t enjoy them, because you learn a ton. Some of my best insights have come from speaking to people and then afterwards interacting with them. Somebody comes up and says, “I’m in this business or I’m in that business.” Or “That point you made — I actually started a company that’s working on that.” And suddenly, wow, you have a new source. So, all those serendipitous things you can’t do now, that I certainly miss.

Barbara Palmer is deputy editor of Convene.