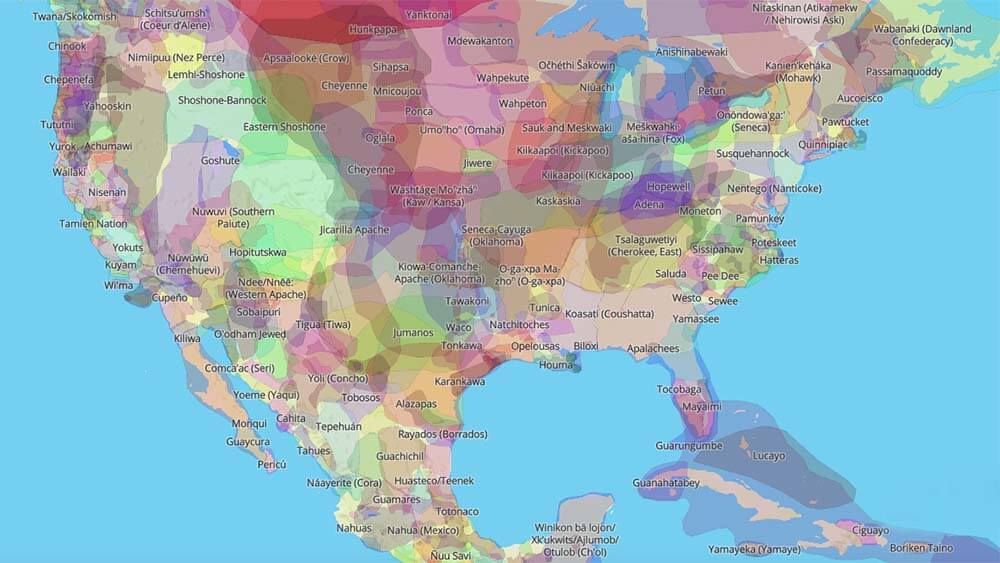

Native Land Digital started in early 2015 and on its website shows an interactive map outlining traditional Indigenous territory boundaries around the world. More events are honoring Indigenous peoples through land acknowledgements. (Native Land Digital screenshot)

Editor’s note: Renowned anthropologist Dr. Jane Goodall has said of the climate crisis, “What you do makes a difference, and you have to decide what kind of difference you want to make.” With that in mind, we are dedicating the November/December edition of Convene fully — our first single-topic issue — to the climate crisis, and what the business events industry is doing to address this global challenge. Find stories from the Climate Issue here, and read our cover story, “A ‘Watershed Moment’ for Events — and the World.”

The practice of including land acknowledgements — spoken and written statements that formally acknowledge the past and present relationship of Indigenous people to the land where activities are taking place — are on the rise around the world. They’re read aloud to begin conferences, they serve as preludes for events ranging from hockey games to the ballet, and have been spotted hanging on the walls of Seattle coffee shops. Last year, for the first time in its 95-year history, Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade in New York City began with a ceremony acknowledging that the event was taking place in the Lenape territory of Manahatta.

But even as land acknowledgements become more mainstream, individuals and groups increasingly are raising questions about their impact and how they are constructed. Members of Association of Indigenous Anthropologists (AIA) recently asked the American Anthropological Association to stop opening conferences with land acknowledgments and a related welcoming ritual, to allow time for a task force to make recommendations. Land acknowledgements often serve as “little more than feel-good public gestures,” AIA members wrote in an article published in Yes! magazine. And while they may be intended to recognize and honor the presence of Indigenous people, by emphasizing Native history and heritage, they wrote, land acknowledgements can have the opposite effect, relegating Indigenous people to a “mythic past.”

Joshua Nelson

From his perspective, land acknowledgements can address history in beneficial ways, said Native American scholar Joshua Nelson, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, and professor of English and director of film and media studies at the University of Oklahoma. They can serve as a reminder that “all of us, or a particular organization, or even a convention center, didn’t get to where they are on their own — whether it’s geographically, economically, or historically,” Nelson told Convene. They can say, “your presence is dependent upon the sacrifices of Indigenous people in the past.”

But land acknowledgements, particularly in the United States, also have a lot to do with countering the many ways that Native people are absent, he said. Often, “they’re not in the room where the meetings are taking place. They are not regarded as present and participating in the active life of our nation.”

If land acknowledgements can serve as regular reminders that Native people are still around, they also can encourage people “to maybe even just look in the room, and see: Are there Indigenous people here?” Nelson said. “[And] if they’re not there, ask why aren’t they there? Because if we’re reminded that they are still present, then maybe we want to know why they’re not participating in this meeting. Were they not asked? Are they on the board of the organization? Are they on the panels? And might there be some ongoing culpability in that ongoing absence?”

Nelson said he would urge everyone who was working on a land acknowledgment statement to consider what their organizations can do to be more inclusive of Indigenous people in concrete ways. For example, as a member of the Committee on Antiracism, Equity and Diversity for the Society for Cinema and Media Studies, Nelson proposed the society waive a year’s membership and conference fees for Indigenous scholars and those working on Indigenous-related projects as a way of making the organization accessible, and then to waive conference fees for those groups for a second year.

The initiative resulted in multiple new members for the society, Nelson said. Importantly, “it showed that the organization had skin in the game and was willing to sacrifice,” he said. As a result, “the society created a much more welcoming space with a kind of a critical mass [of Indigenous participation] that we’d never seen before.”

It’s How You Say It, Too

One of the most frequent criticisms of land acknowledgements is that it is easy for them to become rote — that they are rattled off quickly, as if a box was being checked, said Amy Marshall Furness. Furness, who is non-Native, is head of the library and archives at the Art Library of Ontario and a board member of Art Libraries Society of North America, where she developed the section of the society’s policy manual dealing with land acknowledgements.

“I would say that that ‘time taking’ is one of the most critical things,” she said, “to make sure that as the words are said, they’re said deliberately, not in a hurry.”

RELATED: How Visit Seattle is Honoring Indigenous Peoples

It’s important, too, Furness said, to take the time in order to consider the seriousness of what you are saying. “In creating land acknowledgements, we are adapting a practice that is rooted in Indigenous practices themselves,” she said. “If you were visiting somewhere [as an Indigenous person], you would begin with a thoughtful and spiritual conversation about thanking the caretakers who are letting you be a guest and giving thanks to the Earth. And perhaps the listeners are invited to take a moment to consider their own relationship to the land where they are.”

‘Good Intentions, Good Heart’

Given “centuries of displacement and dispossession, acknowledging original Indigenous inhabitants is complex,” reads a statement on the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) website about the land acknowledgement offered at gatherings at NMAI, where collections represent the entire Western Hemisphere.

“Starting somewhere is better than not trying at all,” wrote Kate Beane, Ph.D., who is Flandreau Santee Dakota and Muskogee Creek, on the website for the Native Governance Center, which represents 23 Native nations. “We need to share in Indigenous peoples’ discomfort. They’ve been uncomfortable for a long time. We have to try. Starting out with good intentions and a good heart is what matters most.”

Learn More

- Native Governance Center, a Native-led nonprofit organization, has published a guide to Indigenous Land Acknowledgement at nativegov.org.

- November is National Native American Heritage Month, which recognizes the significant contributions Native Americans made to the establishment and growth of the U.S.

Barbara Palmer is deputy editor of Convene.