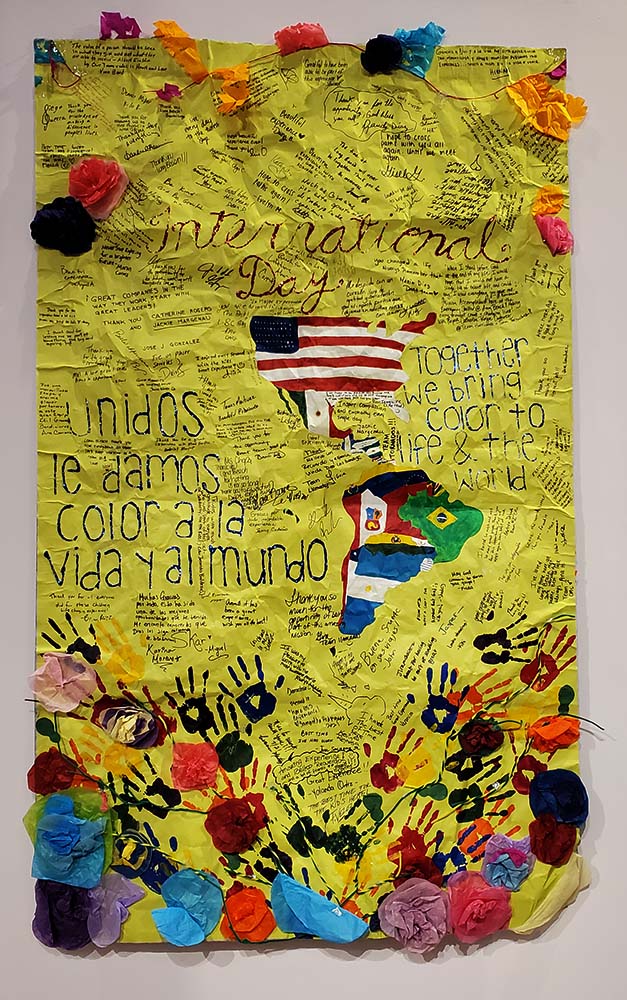

Long Beach’s Museum of Latin American Art displayed an exhibit of artwork made by migrant children living temporarily at a shelter in the Long Beach Convention & Entertainment Center.

At the Long Beach Convention & Entertainment Center (LBCEC), it’s second nature for staff members to help out in whatever ways they can, said Steve Goodling, who has served as president and CEO of the Long Beach Area Convention & Visitors Bureau for two decades. “Long Beach is the smallest big city you’ll ever find,” Goodling added. When clients book space at the convention center, “we don’t just give people the keys,” he said. “We’re part of the team.”

That was true last spring, when the center welcomed the first guests at the convention center after a year-and-a-half — the more than 1,500 young women and children who arrived at the U.S. border as unaccompanied minors were housed at the LBCEC from late April to early August.

Long Beach Mayor Robert Garcia set the tone for the partnership between the city and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) in a press conference at LBCEC held April 22, the day that children began arriving. “It’s incredibly important,” Garcia said, “that we treat every child with compassion, kindness, and with love.”

HHS was responsible for the center’s logistics, including programming education and recreation, but the community and the CVB “really led the charge” on creating a softer experience for the children, said LBCEC General Manager Charles Beirne.

RELATED: Promoting Equitable Access to Tech

The CVB and the city prepared for the children’s arrival by launching a toy and book drive, asking that donations be dropped off at the convention center and at five local hotels. At first, CVB staff used their own cars to pick up the donations, Goodling said. “It just mushroomed,” Goodling said. “All of a sudden, we had to hire a moving truck.” Long Beach and surrounding communities filled the center’s Seaside Ballroom with more than 130,000 items, including 30,000 toys.

The community provided funding for concerts and performances by local musical groups in Spanish and English, and for dance classes, reading labs, and programs presented by the Aquarium of the Pacific. There were visits from therapy dogs and members of the Los Angeles Dodgers baseball team.

The Long Beach community provided funding for programs done in Spanish and English to soften the transition for migrant children staying in the city.

The LBCEC’s lobbies and hallways are furnished with sofas, art, and chandeliers, and Beirne used the center’s gobo lights to project images of butterflies on the walls to further lighten the atmosphere. The city and the center hosted a Fourth of July celebration for the children at the center, with music and food stations and a large screen where the city’s fireworks show was projected. It really became a community affair and “it was fun to watch it because we all are so close anyway in the city,” Goodling said. “It was another reason to come together around something that we all believed in and we did.”

‘Politics Aside’

Hosting the migrant children was a contentious issue nationwide, Goodling said. He recalled a conversation he had with Beirne soon after the children had arrived at the center. “Charlie said to me, ‘Steve, politics aside, they’re kids,’” Goodling said. “I think that’s where Long Beach really came together, because honestly they’re kids and we did what we felt we needed to do for kids.”

Long Beach has a history of supporting refugees and “a duty to help in a major humanitarian effort,” Mayor Garcia told a local newspaper in announcing the shelter. “This is an opportunity for us to model how to do this work.” Garcia was five years old when he moved to the United States from Lima, Peru, and became a U.S. citizen when he was 21.

It was the mayor’s leadership “that helped us bring the children here,” Goodling said. “And then we, as a community, believed in it and rallied behind it. And those children received the Long Beach care that we are known for.”

There was an unexpected benefit to the city and its residents, Goodling said. The shelter brought hundreds of federal workers to Long Beach, who stayed in local hotels, used local ride-sharing businesses, and ate in local restaurants, jump-starting the economy and allowing businesses to bring back workers to local restaurants, hotels, and the convention center, he said. There had been some worry that the convention center might suffer some heavy wear and tear, Goodling said, “but it was actually just the opposite — everyone was very respectful and very appreciative.

“And it could not have been a better transition for [the children]. And quite honestly, a better transition for us coming out of the pandemic, because they were the first group of people that we hosted in 18 months,” he said. The center ceased operating as a shelter on Aug. 1 and the first convention group moved in on Aug. 4.

“All of this transpired,” Goodling said, “by doing the right thing.” .

Barbara Palmer is deputy editor of Convene.