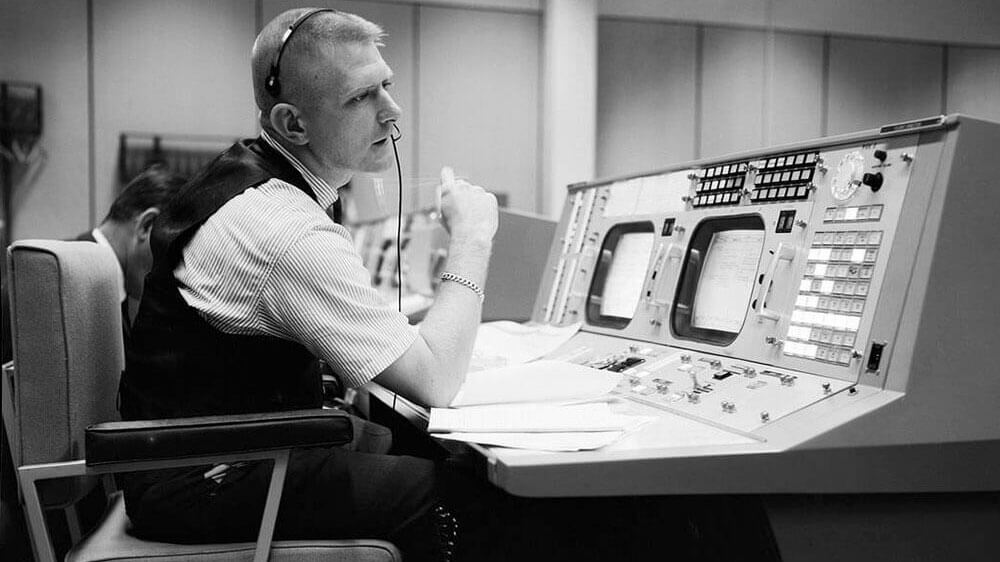

Flight director Eugene F. Kranz works from his console during a May 30, 1965, Gemini-Titan IV simulation at the Mission Control Center in Houston. Kranz will speak at Convening Leaders 2020. (Courtesy NASA)

Business event organizers perform under pressure — to deliver a successful event for attendees, sponsors, and assorted other stakeholders. But what does it feel like when an entire country is counting on you to make the right decisions? As a flight director at NASA, Gene Kranz was in charge of some major events in American space history, including the Apollo 11 lunar landing and saving the crew of Apollo 13 after an oxygen tank failure.

Business event organizers perform under pressure — to deliver a successful event for attendees, sponsors, and assorted other stakeholders. But what does it feel like when an entire country is counting on you to make the right decisions? As a flight director at NASA, Gene Kranz was in charge of some major events in American space history, including the Apollo 11 lunar landing and saving the crew of Apollo 13 after an oxygen tank failure.

And while there’s a world of difference between leading an outer space exploration program and executing a live event, Kranz — who served as a fighter pilot in the Air Force before joining NASA — thinks that understanding how to navigate those high-pressure situations applies to evaluating potential risks and rewards in any kind of role. In advance of his Main Stage presentation on Jan. 7, sponsored by Visit Houston, he shared some of those lessons with Convene.

What’s your advice for how to evaluate the potential risks and rewards when you have to make a decision in an instant?

As a fighter pilot, you practice what’s called the OODA loop — revolutionary tactics taught at the fighter weapons school — [which stands for] Observe, Orient, Decide, and Act, to get inside an opponent’s decision loop. You’re trained to very quickly grasp the big picture, establish your position, pick a path, and execute. A lot of people are smart, but they really struggle with the ‘A’ part of that equation. They delay the execution process.

Gene Kranz today

To avoid those delays, we developed mission rules at NASA. Those mission rules were extensively debated and tested during training before they become something that we all followed. For the Apollo 11 mission, we had over 300 pages of rules. There are several thousand rules that have been rehearsed and reviewed between everyone on the team — the controllers and the astronauts. We develop every product that is used throughout the course of the mission to identify areas were something could go wrong.

There is an excellent book I have used called Crisis Management, written by Steven Fink and produced by the American Management Association. It helps frame those rules as shaped by looking at [a] risk-versus-risk and risk-versus-gain trade. And those formulas apply in public business as well as in mission control. So while you may have to make an urgent decision, the rules have already been set in place to help you make the call.

Our audience leads teams who help execute their events. From your experience leading a team, how do you create an effective communication flow between everyone — to ensure that everyone has access to the right information to make an informed decision?

At the beginning of each shift and at the ending of each shift, every flight controller receives a handover from the prior shift. So, for example, on the lunar landing day, we had not been on shift for nearly 30 hours. My team had a lot of reading to do to get caught up and understand the notes from those working before us. It’s designed to be a highly integrated process that allows everyone to ask colleagues for input and ideas.

This model is not reserved solely for high-pressure [situations], though. I was the director of around 6,000 people at one time, and I used the same process in non-mission timeframes — to develop budgets and establish organizational direction. A team operating in a horizontal fashion develops integrated answers that effectively leverage everyone’s expertise.

Gene Kranz (center) discusses the Apollo 17 lunar landing with flight directors Neil Hutchinson (left) and Gerald Griffin in the Mission Operations Control Room during a Dec. 6, 1972, launch delay. (Courtesy NASA)

While everyone can weigh in on a decision, the ‘go or no go’ call typically rests on one person’s shoulders. If the decision winds up being incorrect, should one leader accept responsibility? Or should the wrong call be owned by everyone?

There are very few failures that are identified to a single individual or a single small group. Referring back to [Fink’s book] Crisis Management, there are certain indicators prior to a catastrophic event that are symptoms. The question is whether you are good at looking at those symptoms.

And in the cases where those symptoms aren’t diagnosed early, how the culture and the expectations of the organization change [to avoid another failure] are what’s most important. After the Apollo 1 fire [a 1967 accident that killed three crew members], we sat down and wrote a set of Foundations Statements to correct the areas where we failed.

The Foundations Statements instill the sense of duty to step forward, and [they remind everyone to] always be aware that, suddenly and unexpectedly, you may find yourself in a role where your performance has ultimate consequences.

You had mission rules, but there was no model to follow for the first moon landing. What’s your best advice for teams trying to do something that has never been done before?

When I first arrived at NASA, I had been a flight test engineer on the B-52. I knew nothing about rockets and nothing about spacecraft. But I had run other complex projects with safety concerns and complicated technical issues. I had been there for two weeks and was sent to the Cape [Canaveral] to write the countdown for the first rocket. It was a question of applying previous experiences and then learning by doing.

If an entire organization wants to do something big and bold, you have to get others to buy into that value of learning by doing. But you also have to get accountability at the lowest level you possibly can. Leadership must have the confidence in those people and their knowledge, too. Sometimes, the leader has to accept the position that somebody else is carrying the ball. In those cases, it’s the leader’s job to say, “How can I help you?”

David McMillin is an associate editor at Convene.

Gene Kranz will speak on the Main Stage at PCMA Convening Leaders 2020 in San Francisco, at 3:15 p.m. Jan. 7. His appearance is sponsored by Visit Houston, hosts for PCMA Convening Leaders 2021.