Attendees arrive at the Fyre Festival only to discover that the luxurious accommodations they were promised did not exist in this scene from the Netflix documentary “FYRE: The Greatest Party that Never Happened.” (Netflix)

Two documentaries that chronicle the Fyre Festival currently are streaming online, resonating with the planner community: Fyre Fraud on Hulu and FYRE: The Greatest Party that Never Happened on Netflix.

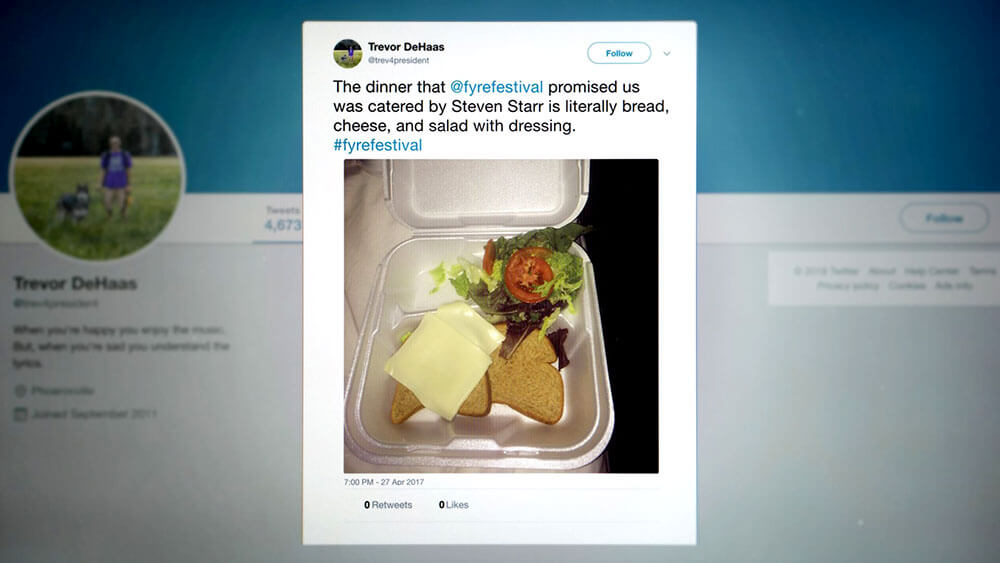

To recap the festival’s spectacular failure: In 2017, thousands of people, lured by social-media campaigns featuring bikinied supermodels partying with musicians on white-sand beaches in a tropical paradise, paid hundreds and hundreds of dollars for tickets to what was billed as a luxury music festival over two weekends in April and May on an island in the Bahamas. The festival was canceled within hours after the first guests arrived at the chaotic, unfinished festival site, where there was insufficient food, water, transportation, security, and housing for the expected crowds.

One of the widely reported side effects of watching the documentaries is schadenfreude, the German term for the guilty pleasure that comes from seeing others’ misfortune — in this case, watching those with the means to pay thousands for what was to be an exclusive, celebrity-studded event ending up instead eating cheese sandwiches and scrambling for spots in tents.

The reaction of meeting professionals — who put themselves and their colleagues in the shoes of the event producers and other vendors associated with the disaster, not the partyers — tended more toward the dumbfounded, judging by comments on an industry-only online forum. There was disbelief at the magnitude of the logistical incompetence on display, colored by outrage at the disregard for the risks that attendees and vendors were exposed to by the organizers. “SMH [shake my head] about a thousand times,” wrote one conference organizer. “I watched with my mouth open in amazement,” wrote another.

Fyre Festival creator Billy McFarland, shown here in “Fyre Fraud” on Hulu, currently is serving a prison sentence for fraud. (The Cinemart/Hulu)

And there was much in the Netflix documentary (Convene did not see Fyre Fraud) to cause a meeting planner’s jaw to drop: Billy McFarland, a young entrepreneur who conceived of the event to market a musician-booking platform, compressed the timeline for planning a festival — typically a year — to a few short months. The festival already was being advertised when organizers lost their first site, a private island; they then scrambled to find another island. The organizer dismissed concerns from those working with him that the available housing and food were inadequate, and that the site could never be ready on time. He failed to pay local workers who labored around-the-clock trying to make the deadline.

When the first attendees arrived at the unfinished site, organizers stalled for time by taking them by bus to a beachfront restaurant where the young attendees were plied with alcohol. (McFarland didn’t pay that caterer either.) “When the event really turned into a fiasco” — with nowhere to sleep, no food, but lots of liquor — “they were really lucky,” wrote one planner, “that no one died or was assaulted, raped, or killed.”

Given McFarland’s behavior in the months leading to the event — he currently is serving a six-year jail sentence for fraud — planners suggested that the festival was the kind of gargantuan train wreck that savvy event professionals would have seen coming a mile away. “Red flags were going up for me from the very beginning,” wrote one planner. “It was evident to those of us who do and have done this for a living that there was no one with major event, logistical, off-grid experience in charge, or even brought in for input.”

Some commenters put some of the blame on vendors. It was “incredibly irresponsible” to work with McFarland, one wrote. “Why didn’t all of the vendors bail and start legal proceedings way earlier than they did?” wrote another.

This Fyre Festival ad shows some of the many broken promises of the festival. (The Cinemart/Hulu)

And why did the New York City–based event producer Andy King, who worked on the festival, “hitch his wagon to McFarland when all the danger signs were more than apparent?” asked one planner. (King ultimately exited the festival scene as it was still unwinding, hidden in the back seat of a car.)

That planner commenter, a CMP, recalled a heated conversation she had with a colleague about who ultimately bore responsibility for the safe execution of an event — the client or the event professional. Her view, she wrote, was that “the onus was on me as the planner at the end of the day to professionally guide the client with safe design and execution. Sometimes the best thing we can do for all concerned, so far as it is within our power, is to walk away and not take the assignment or dig in our heels for the safety, both physically as well as financially, of all concerned.”

In short, another planner wrote: “They needed an adult and none were to be found.”

There is one bright spot in the disaster: A GoFundMe account started by Maryann Rolle, a caterer featured in the Netflix documentary, raised more than $200,000 in 11 days — more than enough to share with other workers defrauded by the festival organizer.

More Fyre Festival and Other Badly Planned Events

This Might Be the Worst Event-Planning Crisis in Recent History

4 Really, Truly, Poorly Planned Events

One of the many tweets from the Fyre Festival shows the disappointment attendees felt. (Netflix)