The Nest Summit 2020, organized by NXT Events Media Group, took place in the new virtual event studio at the Jacob K. Javits Center in New York. (See “Building the Nest” at bottom of page.)

In November 2019, during what turned out to be the final weeks of a pre-COVID-19 world, the European Biological Rhythms Society (EBRS) and the Institute of Medical Psychology at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich (LMU Munich) jointly held a conference to test the use of virtual technology.

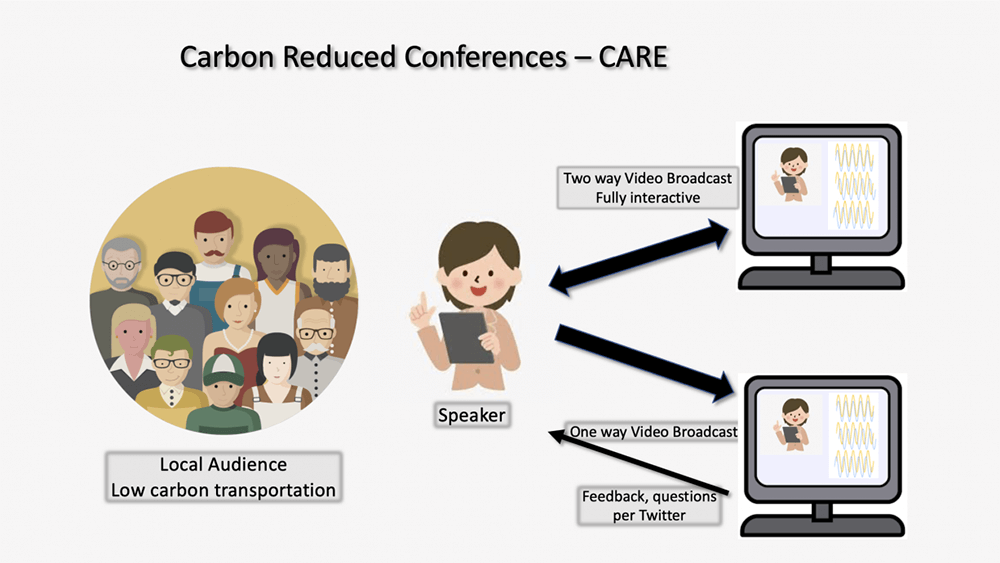

Their goal in moving the conference’s content online — compared with the thousands of conferences forced to move online in the wake of the travel restrictions and health risks brought on by the pandemic — was to experiment. Organizers of the CAREebrs Conference 2019 — CA for carbon, RE for reduction — designed a hybrid/virtual model to lessen the environmental impact of travel to conferences while still preserving the benefits of in-person events.

The conference agenda consisted of five hours of content — a plenary, and six short talks that were repeated before and after the plenary — to accommodate participants in 18 time zones. Speakers and participants were connected by interactive video to five hubs: Israel’s Tel Aviv University, Switzerland’s University of Zürich, Massachusetts’ Harvard University, Japan’s University of Tokyo, and Brazil’s Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul. There also were 69 hubs where participants watched livestreamed sessions, asked questions, and commented on Twitter.

The model represented “a new mechanism of conferencing — we have to ‘learn’ this,” the organizer, Martha Merrow, a circadian biologist at LMU Munich, told potential attendees in a Tweet announcing the conference. Such “new formats,” she added, “will unlock new knowledge leading to innovation.”

Along with scientists, the conference included researchers from LMU Munich’s psychology department, who measured the quality of interaction and networking among participants meeting in the hybrid and virtual models. LMU professor Anne Frenzel, whose research specialties include studying how emotion affects teaching and learning, led the conference evaluation.

The results of Frenzel’s analysis are still pending, but “at first glance, it seems to have been more successful than I had dared hope,” Merrow told Nature. “It was possible to have fluent scientific discussions,” she said, and some hubs organized local social events after the meeting. Along with saving carbon emissions, the conference, which drew participants from 32 countries, also made the content accessible to those who may have been unable to travel to an in-person event because of time constraints or lack of childcare, Merrow said. Approximately 450 people participated — about 10 percent more people than attended EBRS’s main conference held earlier that year in Lyon, France.

Organizers of the CAREebrs Conference 2019 demonstrate their CARE conference format with this illustration.

The ‘Best Future Strategy’?

Nature called the chronobiology conference one of the first to take a research-based approach to designing conferences that reduce travel — and carbon emissions — while seeking to preserve and quantify the benefits of the in-person interaction. Morressier, a Berlin-based company that provides a platform for virtual and hybrid conferences, similarly advocates a “best of both worlds” meeting model. “We strongly believe that a hybrid approach — including a live, in-person event and virtual online component — presents the best future strategy for most conference organizers,” said Lauren Kane, Morressier’s chief strategy officer.

Morressier specializes in academic and professional conferences, an arena where “human connections forged via a chance discussion over drinks, or an astute comment whispered in a lecture audience,” are key, Kane said. At the same time, “a hybrid approach embraces the benefits offered by virtual conferences, including greater flexibility, accessibility, and global inclusivity.”

Well before the pandemic, scientists were calling for new ways to think about scientific conferences. Brian Lovett, a post-doctoral researcher at West Virginia University who specializes in vector biology and mycology, has argued that technology should be leveraged to effectively bring the offline and online realms together. Prior to COVID-19, Lovett was campaigning for a revamped conference system, one that includes virtual capabilities to foster impactful scientific discourse and broadcast a broader range of voices. (Lovett was the co-author of an opinion piece — “Science Conferences Are Stuck in the Dark Ages” — published in WIRED last January.) Until now, most changes have been incremental, “such as the addition of a new kind of session or an app that holds the scientific program,” Lovett said in an interview published on Morressier’s website.

“There is room for bolder changes that open the doors for more to participate and reimagines the format of scientific sessions to be more dynamic, instead of trying to simply transition what has been done onto a video conference.”

In September, neuroscientist Chloe J. Jordan, an instructor at Harvard Medical School, and Abraham A. Palmer, a professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego, co-authored an article, “Virtual Meetings: A Critical Step to Address Climate Change,” in Science Advances. “We are only a few months into the changes wrought by the novel coronavirus, and already many of us have learned enormous amounts about the challenges and opportunities associated with holding online meetings,” they wrote. “As the pandemic continues, virtual meetings are replacing traditional meetings that required air travel, thus dramatically reducing the carbon footprint of these meetings. Can we get the same results from virtual meetings?”

Some meeting features are difficult to replicate online, they wrote, but “academics and professionals are becoming increasingly proficient in virtual conferencing tools, such as break-out discussions, digital poster sessions, virtual white boards, real-time chat functions, and informal post-meeting ‘social hours,’ thus reducing our reliance on in-person networking for professional development. … Although none of us wished for it, this pandemic has forced us to rethink meetings and to begin the inevitable process of experimentation, with the requisite successes and failures. We must continue these experiments even when the threat of the current pandemic recedes.”

Barbara Palmer is deputy editor of Convene.

The COVID-19 pandemic led to “tremendous demand: to participate in The Nest Summit 2020, said Sharon Enright, president of NXT Events Media Group.

Building the Nest

By Casey Gale

“The Nest” was launched in 2019 by the Jacob K. Javits Center, The Climate Group, and NYC & Company as a one-day conference to bring together organizations looking to hold meetings during Climate

Week NYC, an event hosted in association with the United Nations and the City of New York.

The Nest Summit 2020, organized by NXT Events Media Group, grew to a five-day hybrid event that featured more than 100 thought leaders from business, government, research, nonprofits, and other sectors. The event’s content, delivered virtually and partially filmed at Javits Center’s recently unveiled broadcast studio, has been viewed by more than 12,500 people.

The COVID-19 pandemic has created new awareness about the vulnerability of the human condition and led to tremendous demand to participate in The Nest Summit 2020, Sharon Enright, president of NXT Events Media Group, told Convene.

“The pandemic has had a huge impact on daily life in virtually every part of the world,” she said. “As such, it has brought new urgency and understanding to just how devastating unaddressed climate change will be and the fact that if we cross the tipping point in climate change, there will be no clear or easy solutions.”

Casey Gale is associate editor at Convene.