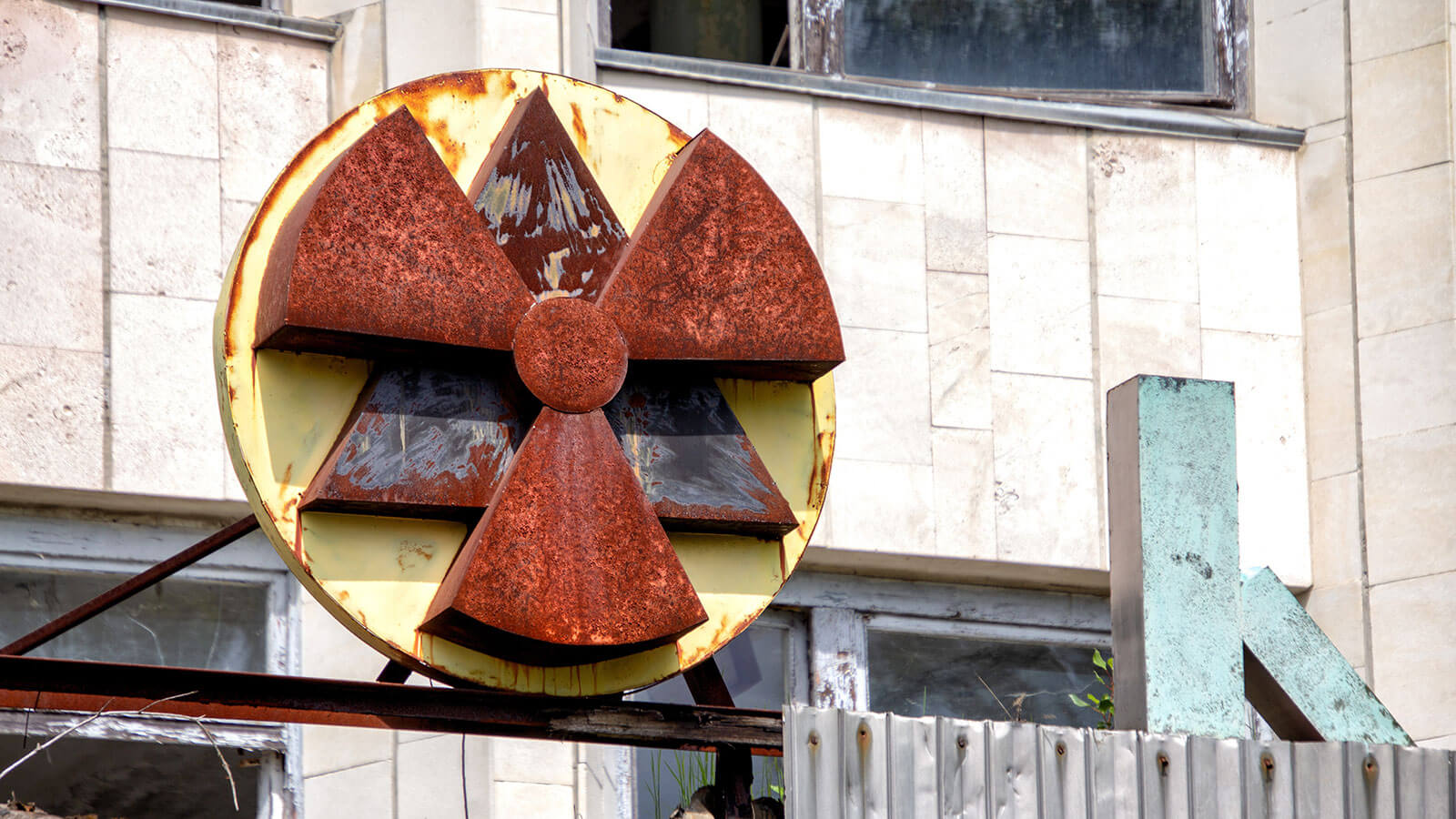

HBO’s 2019 miniseries “Chernobyl” is inspiring a tourist wave to the site of the 1986 nuclear disaster (above) and nearby Pripyat, Ukraine. Interest in “dark tourism” has grown in recent years. (Yves Alarie/Unsplash)

When Karel Werdler was working as a tour guide in Germany, he noticed a curious trend. “Very often [tourists] wanted to see things that I thought were not really in line with the expectations of tourism,” said Werdler, who now works as a senior lecturer of history at InHolland University in the Netherlands. “They wanted to see, for instance, battlefields or cemeteries. And I thought it was actually kind of weird, that when you’re on a holiday looking for a sun, sea, and entertainment, you want to see something that is related to death.”

The frequent interest in these dark sites led Werdler to discover the concept of “dark tourism” — defined as traveling to destinations associated with death, tragedies, and the macabre.

“So very often, people would say, ‘Okay, we are going to Germany. We actually would like to see something like a former concentration camp.’ I’d take them to Dachau in the afternoon. And the crazy thing was that in the evening, after visiting a terrible place like that, we went to the Hofbrau house where everybody was enjoying this beer,” Werdler said. “So there was always a kind of a dualism, you might say, in my experience.”

Holocaust memorial sites are some of the most popular dark tourism destinations — in 2018, Auschwitz experienced a record two million-plus visitors.

“Of course, that was not created as a tourism site,” Werdler said. “Obviously it’s a memorial, but it attracts millions of people, and it’s only getting bigger.”

Tourists walk through the Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial in Colleville-sur-Mer, France. Commemorations of important historical events, like the World War II D-Day invasion, draw tourists to a destination. (Sergey Nemo/Pixabay)

According to Werdler, other popular dark tourism sites include the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam, the National September 11 Memorial & Museum in New York, and the Khmer Rouge Killing Fields in Cambodia. “Chernobyl is also hot at the moment, after the HBO series,” Werdler said. A recent CNBC article reported that the site of the nuclear disaster expects to see 100,000 visitors in 2019 — a significant spike from 70,000 visitors in 2018. When dark tourism sites hold special events commemorating what happened — for instance, the landings at Normandy in World War II — “a lot of people want to be there,” Werdler said. “It has really become a business. I did some research there myself, and found 27 museums, just in Normandy, dedicated to D-Day.”

Despite the growing interest in dark tourism — something that can be proved, according to Werdler, by the sheer number of print and television interviews he has done in the past several years on the subject — he said many destinations are hesitant to lean into being called a “dark tourism site.”

“It’s kind of a strange situation, because the connotation ‘dark’ is negative in general,” Werdler said. “And there’s quite a few businesses and locations that don’t want to be a dark tourism location. So we use other words like ‘battlefield tourism’ or ‘memorial tourism or ‘political tourism.’”

Werdler said he cautions his history students against using the term ‘dark tourism’ when approaching a destination for research, but also believes the name undeniably attracts attention, whether the destinations themselves approve of the phrase or not, “because it sounds a bit weird, a bit spooky,” Werdler said. “And that of course is interesting for the average visitor, and explains the popularity of television series [like ‘Chernobyl’].”

Werdler also has noticed a rise in interest in the academic and tourism sectors as well, with more tourism-related conferences featuring tracks in dark tourism. “You might say it’s niche tourism that can be related to dark, and researchers are always looking for a platform to share their ideas and their findings,” he said. “And then the ethical question always comes to mind: Should you present a [destination] like this? And why should you present it? Who are you dealing with? Who are your stakeholders? It’s often very complicated, and so that makes it interesting for researchers.”

Casey Gale is an associate editor at Convene.

‘Dark Tourism’ Destinations

The National September 11 Memorial & Museum in New York is a popular "dark tourism" site. (Brittany Petronella/NYC & Company)

The Pripyat amusement park was set to open May 1, 1986, but the April 26 Chernobyl disaster prevented it from ever opening. (Ilja Nedilko/Unsplash)

The Anne Frank House in Amsterdam is a museum dedicated to the wartime diarist who wrote about her life hiding from Nazi soldiers. (Cris Toala Olivares/Anne Frank House)