Scholars and computer scientists recently deciphered Charles Dickens’s version of shorthand with a little help from Zoom and Eventbrite. (Public domain)

Claire Wood, a lecturer in Victorian fiction at the University of Leicester in England, and Hugo Bowles, an English professor at the University of Foggia in Rome, waited until Charles Dickens’ Feb. 7 birthday to share some big news: Thanks to their shared initiative, a letter written in coded shorthand by the English writer and social critic in 1859 had finally been deciphered.

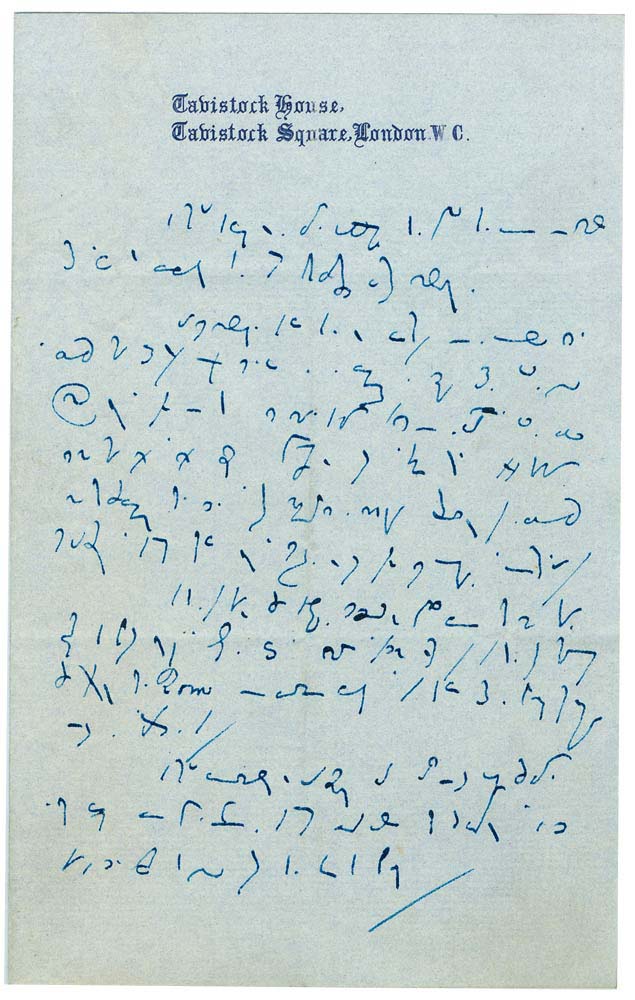

As a court reporter and parliamentary reporter early in his career, Dickens had developed a personal system of symbols, dots, and scribbles for quick note-taking that became indecipherable to others. This particular letter written in his code, which is held in the archives of the Morgan Library and Museum in New York City, had puzzled scholars for more than a century. The code was finally cracked by a group of Dickens experts and computer scientists who worked together in a three-part series of online sessions convened by Wood and Bowles.

It was a literary milestone, but what caught my attention was how the mystery was solved with the kinds of digital tools — Zoom and the online registration platform Eventbrite — that have been in daily use by many in the meetings industry over the last two years. The digital tools offered the academic community the same advantages discovered by those who organize meetings of all shapes and sizes: the ability to reach a larger and more diverse audience and to leverage their combined expertise.

Bowles had tried on his own for years to decode the Dickens letter — which turned out to be a request for a London newspaper to run an advertisement that the paper had rejected. But like other scholars who had tried to decipher the letter over the decades, he hadn’t made much headway, the professor told The New York Times.

Late last year, after Bowles and Wood issued an open invitation to interested parties to participate in three free online sessions dedicated to solving the code, 1,000 people signed up via Eventbrite. Approximately two-thirds of the participants were Dickens experts, and a third were computer scientists, said Wood. To the surprise of many, the person who decoded the most symbols and was declared the winner of a $406 prize (300 British pounds) offered by the University of Leicester was not a literary scholar, but a computer technical support specialist — Shane Baggs from San Jose, California. Baggs has never read a Dickens novel.

It was the combination of people collaborating from literary and computer science backgrounds which helped to break new ground, Wood told the Times. Scholars from previous generations didn’t have access to the teamwork enabled by crowdsourcing technology, she added.

A portrait of Charles Dickens by photographer Jeremiah Gurney, circa 1867-68. (Public domain)

Neither Eventbrite nor Zoom, founded in 2006 and 2011, respectively, are new, but such broad access to both — particularly to Zoom — is a recent result of the pandemic. The cancellation of in-person meetings during the two years of the pandemic has yielded a huge increase in the numbers of users of digital platforms, as well as a burst of experimentation in new formats, like the literary code-breaking sessions.

Digital platforms could prove to be a time- and cost-effective avenue for additional experiments in interdisciplinary collaboration, accelerating a trend that precedes the pandemic. For example, the Manova Summit health-care conference, held in 2018 and 2019 in Minneapolis, Minnesota, went out of its way to create new intersections between participants with shared, but not identical interests, inviting participants in multiple health-care sectors and adjacent industries, including fitness, food, the environment, to engage in conversations on the future of health care.

“Most conferences are more vertical, right?” Kathy Tunheim, one of Manova’s organizers, told Convene in 2019. They’re “people who are all in the same kinds of job. Or they’re horizontal — they’re all in the same kind of roles across companies. And what we’ve done is created a place for intersections that most of the people told us that they were meeting and hearing from people that they just haven’t had the opportunity to intersect with before.”

The success of the collaboration between the shared interests and complementary expertise of the Dickens scholars and computer scientists is an argument for the expansion of multi-disciplinary experiments, both online and in person. Digital tools didn’t solve the puzzle that had eluded scholars for more than a century. But the tools amplified the ability of Wood and Bowles to reach a goal familiar to meeting organizers: getting the right people into the room, virtual or otherwise.

Add AI and Mix

Interdisciplinary scholarship and conferences are nothing new, but as with so many other trends in COVID times, their numbers have massively accelerated, said Sami Benchekroun, cofounder and CEO of Morressier, a virtual conference and publishing platform that specializesin scientific and academic conferences.

People are using online platforms to experiment with creating new interdisciplinary conferences, and new revenue streams and communities, Benchekroun said. “We see gazillions of new, smaller conferences and smaller groups meeting online and just testing the waters.”

The most common combination is a mix of computer science with other disciplines, “such as AI in cardiology, AI in ophthalmology — the combination of artificial intelligence and something else in life sciences or social sciences, or art,” he said. “But there’s all these different, great examples where sciences are coming together. And it feels like the world became much closer together due to the pandemic, because everything is just at your fingertips.”

Barbara Palmer is deputy editor of Convene.