Delegates gather at the U.S. Food Waste Summit.

In June 2016, the Harvard Law School Food Law and Policy Clinic (FLPC), in partnership with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection, hosted the largest-ever meeting solely focused on finding ways to save the 40 percent of food in the United States that goes to waste.

It’s an urgent issue, as Mathy Stanislaus, assistant administrator for the EPA’s Office of Land and Emergency Management, underscored at the Reduce and Recover: Save Food for People conference. “Wasted food is a failure of the system,” he said at the event, as reported in a post on waste-management publication site Waste Dive. “It’s a societal breakdown of valuable product being thrown away. How do we really make this resonate? How do we really tip this in society?”

For organizers of the 350-attendee event at the Harvard Law School campus in Cambridge, Massachusetts, bringing the problem to a tipping point meant extending the conversation beyond the two-day gathering of food business leaders, policymakers, capital providers, innovators, advocates, nonprofit organization members, researchers, students, and more.

Attendees were encouraged to join together in “working groups” to continue the discussion and brainstorm solutions to the most prominent issues related to food waste — and they didn’t let that opportunity go to waste, according to Katie Sandson, clinical fellow at Food Law and Policy Clinic and an organizer of the event.

“In the two years following the conference,” Sandson said, a group that focused on food safety for donations “worked to conduct a 50-state survey of state food-safety officials to learn about existing state-level food safety-related regulation and guidance that may impact food donations.” The survey was the first to provide such data about food safety for donations on a national scale.

Several of the other groups also continued working together after meeting in 2016, with some hosting webinars or taking on research and policy projects, Sandson said. So when FLPC hosted a second iteration of Reduce and Recover, the U.S. Food Waste Summit, held on June 26–27, 2018, not only did they bring it back to the Harvard campus, organizers reinstated the working-group initiative — which Sandson called “one of the most successful elements of the 2016 Reduce and Recover conference.”

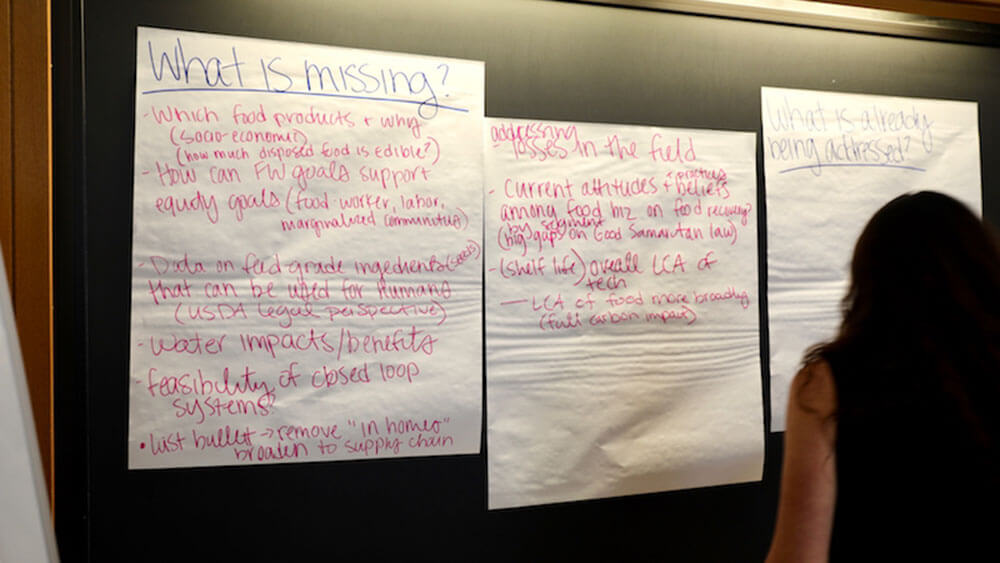

Delegates at the U.S. Food Waste Summit joined working groups to come up with solutions to issues.

Meeting for Change

The U.S. Food Waste Summit, hosted in collaboration with food-waste organization ReFED, encouraged attendees — the event sold out at the 350-person maximum — to join working groups that interested them most. Group topics this year included “Bridging the Food Waste Research Funding Gap”; “Building Infrastructure for Farm Level Surplus”; “Accelerating Date Label Standardization”; and “Organic Waste Management & Policy.”

Additionally, groups were asked to build upon ideas that came out of the 2016 working groups. The groups met for two 90-minute periods between educational sessions. “The first meeting provided an opportunity for attendees to introduce themselves and begin exploring the challenges and opportunities of the particular issue area,” Sandson said, “while the second meeting focused on identifying solutions and opportunities for collaboration going forward.”

During the course of the two-day meeting, each group was asked to answer such questions as: “What federal policy options can decrease wasted food?”; “What private sector actions can decrease wasted food?”; and “What are the opportunities for innovation in this area?” Participants also were asked to identify steps and potential collaborations that could be put into action within the next year to resolve issues related to their topic. The groups then reported their ideas back to fellow attendees and speakers — including representatives from Feeding America, World Wildlife Fund, the James Beard Foundation and Whole Foods Market — during the event’s closing plenary.

“Ultimately, the actions taken will depend on each individual working group,” Sandson said, “but our hope is that several of the groups will continue to meet and work on actionable items, as was the case following the 2016 Reduce and Recover conference.”

Organizers also worked to ensure the conference practiced what it preached throughout the event by providing meals and snacks that featured ingredients that would have otherwise gone to waste, such as “seconds produce, over-ordered products, and surplus snacks recovered from local businesses,” Sandson said. The food highlighted “the variety of sources and causes of wasted food from across the food system,” she said, “and it was also delicious.” The hope, she added, is that “attendees will be inspired to do something similar at their own events.”

As an organizer of the event, Sandson said she was thrilled to see how eager U.S. Food Waste Summit attendees were to network and collaborate with one another in person. “We hope attendees came away from the event with new perspectives on how we can work together across sectors, because it will take partnerships and collaboration to address the issue of food waste.

One actionable takeaway for us,” she said, “is to continue pursuing opportunities to partner with other leaders in this field to host future conferences and events.”