In her book The Art of Gathering, Priya Parker says that when the focus of a gathering is about the “stuff” of the event, “we inadvertently shrink a human challenge down to a logistical one.”

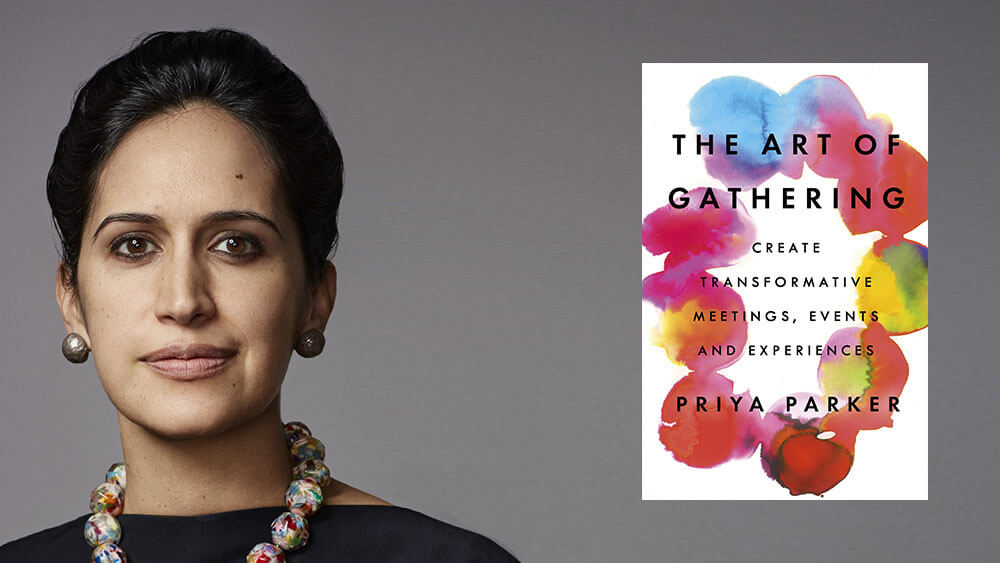

Perhaps it was inevitable, as she writes in The Art of Gathering, that Priya Parker would become an expert in conflict resolution. Her mother, who is liberal, is Indian, and her father is a conservative Midwestern American. Parker was born in Zimbabwe, and lived with her parents in locales including remote fishing villages in Asia and Africa before they got divorced.

As an undergraduate at the University of Virginia (UVA), Parker not only was “anguished” by the divisive state of campus race relations, she fielded constant questions from others about her own racial identity. Her experience led Parker to study what lies at the heart of how groups interact with one another.

At UVA, Parker was a cofounder of the Sustained Dialogue Campus Network, which uses a small-group process to facilitate difficult conversations. She went on to study organizational design at M.I.T., and public policy at Harvard Kennedy School, and has worked on peace processes in the Arab world, southern Africa, and India. Parker is the founder of the Brooklyn-based Thrive Labs where she works with clients who range from luxury retail brands to museums, and from a billion-dollar transportation company to conferences, including the World Economic Forum.

“In every context, I help people solve problems through a group experience,” Parker said over a ginger soda in a Brooklyn coffee shop during an interview with Convene. “That’s the core common thread. What I care about in any group experience I’m a part of, in addition to solving the problem, is that I’m also helping build a temporary community and a sense of belonging to that larger purpose with the people who happen to be in the room.”

In The Art of Gathering, Parker shares what she has learned in 15 years of studying and creating gatherings designed to transform individuals and communities. Her book also serves as an alternative to meeting advice centered on what she calls the mechanics of gathering: “PowerPoint, invitations, AV equipment, cutlery, refreshments.” When the focus is on the “stuff” of gathering, she writes, “we inadvertently shrink a human challenge down to a logistical one.”

For the book, Parker interviewed more than 100 “gatherers,” including conference organizers and event planners, but also Quaker meeting clerks, circus choreographers, Japanese tea ceremony masters, rabbis, coaches, and choir conductors.

For the book, Parker interviewed more than 100 “gatherers,” including conference organizers and event planners, but also Quaker meeting clerks, circus choreographers, Japanese tea ceremony masters, rabbis, coaches, and choir conductors.

How would you describe the role of communication in your work?

There are many ways to create memorable experiences and memorable group experiences. My training is in group conflict resolution and the way I learned is through group dialogue. The heart of my book — the shorthand — is group dialogue for meaning. One of the ways we create meaning is through conversation. The DNA of this book is: How do you communicate more effectively and meaningfully? Both in terms of framing why you’re bringing people together, and in creating a framework so that people are connecting meaningfully.

Is your process the same for all of your clients?

In almost all of my work — [with] companies, organizations, political groups — the question that I always start with is: What is this group trying to solve? To put it in the language of the book, what is the purpose of this gathering? Are you trying to align? Are you trying to show differences? Are you trying to build a community? Are you trying to separate the wheat from the chaff?

You don’t make a distinction in your book between gatherings that include your neighborhood friends and the World Economic Forum.

Human dynamics and group dynamics are the same everywhere. Size changes what happens in a room and context deeply matters, but the same skills and lens that I use to think about what goes into creating a meaningful, connection-filled block party are the same questions that I ask to think about how do you create a meaningful, connection-filled World Economic Forum. They end up looking radically different. But the set of questions is the same.

In the index of your book, the words “food,” “décor,” and “environment” don’t appear, but I found eight references to the word “embodiment.” What do you mean by embodiment?

Embodiment, to me, means creating, in both psychological and physical ways, an experience that represents the ideas that you’re trying to help people explore.

It’s not that I’m anti-food. It’s not that I’m anti-décor — I like a beautiful place as much as the next person. But everything that you create in an environment should serve the purpose of the gathering. And the parts of a room setup that I am interested in are: How do you physically set up space so that the room is working for your goals? Last week, I ran a 400-person gathering experience for an organization. I had asked for the whole room to be in a circle — a giant 400-person circle — and the hotel where the company was hosting the gathering couldn’t do it. They sat people at 40 round tables — 10 people at 40 tables. I got up and started the experience, and said, “Now, usually I do this in a big circle but we weren’t able to do it this way. Can you please — let’s stand up and see how it goes.” And, on their own, everyone got up from their tables, moved out and created a 400-person circle with the tables in between them. And it was awesome.

So part of the idea of embodiment and physical format is first, to not accept the default structure that you’re given, but instead to design for connection. And to create a physical environment that nudges people in the direction that you want them to go.

Would you talk about the role of learning at conferences?

I think most conferences assume that people want to come and learn; it’s the excuse to get people there. But I think we tend to over index on estimating how much people want to learn versus how much they want to connect. At most industry conferences, even ideas conferences, I think we rely too heavily on the crutch of learning and under rely on how much people want to tap into each other.

There’s an assumption that we can only learn from experts on the stage and not necessarily from the people on the floor. The art of gathering applies very deeply to conferences and how people begin to understand [the questions]: Why are [attendees] coming? What do they really want? And what’s the right mix between expert-led sessions and time to meaningfully connect and/or learn from one another?

The unconference, Tim O’Reilly’s Foo Camp, or all of these open-space technologies [or methods] — there are a lot of 20-year-old technologies that create structure beyond the panel or beyond the speaker on the stage. And think innovatively about how do you creatively, with structure, gather differently with 500 or 1,000 people in the room.

Is there a place for videoconference calls at your company Thrive Labs?

Videoconference calls, webinars, even audio conference calls, they’re all gatherings. I’m more interested in in-person gatherings, but many of the principles apply in the same way: openings and closings, the need to moderate. Are you allowing informal small chat at the beginning or is everyone silent? Are you cracking jokes or are you just waiting for everyone to get on the call? Are you having people introduce themselves or are you marching straight into the agenda? Are you starting with logistics? Can you start a conference call or video call where you somehow help people remember that they are all in physical places?

One example: Start a conference call or video call by having each person show the coffee mug they’re drinking from. Find small rituals or hacks that you can start or end your meeting with, like asking, “What’s the view outside of your window right now?” Certain things that actually embody the principles I think of as the art of gathering, which is: We are still people here at the other side of this technology. How do we remind each other of that before we begin?

You write in The Art of Gathering, “we spend much of our time in uninspiring, underwhelming moments that fail to capture us, change us in any way, or connect us to one another.” What are some examples of events that bring large groups of people together in ways that are not bland and boring?

I think The Feast [dinner gatherings] does that very well. Creative Mornings does this — you wouldn’t think of it as a conference, but they create two-and-a-half–hour experiences every month for people who don’t necessarily know each other.

I think different conferences get different parts right and then get imitated. For some time TED disrupted the conference assumption that an interesting talk has to be an hour. Right? The idea that an 18-minute talk is a “long TED talk” has now spread across the world, even beyond TED. The idea that not only can you get interesting content into a five-, eight-, 12-, or 18-minute format, but that it’s better for both the audience and the speaker.

RELATED: Group Interactions, By the Magic Numbers

Does TED do community connection well? Maybe not. But we have learned from them that a full hour with someone talking may not be the best way to spread an idea. That’s valuable. Burning Man has given to the world the idea that you can create a temporary alternative world — you can create a set of rules, share it on your website, and that people agree to, which is that it is a giving economy. You can’t sell things there. That’s an extreme, but very interesting, example. But I think it’s an interesting gift to the world to realize that you can create temporary, alternative worlds to see if we could live differently.

So I think different conferences and different gathering formats have given us, at their best, a demonstration of how to do something well. The problem is when people think, “Okay, I’m going to replicate TED.” We keep making the mistake of replicating formats. First ask what the purpose is and then find your format.

You write in the book about designing gatherings as worlds that will only exist once.

Event planners may think that they are being efficient, as well as transformative, if they take what they did before — see what worked and what didn’t — and retool. I think they are being efficient. There are at least two parts of being an event planner. There’s helping a client understand the purpose of the gathering — the philosophical part of your responsibility — and then I think there’s the logistical part of the responsibility. All I’m saying is don’t lead with the logistics. Event planners are some of the best logistics managers in the world, but most event planners I’ve spoken to didn’t get into it for the logistics. They got into it because they believe that events can do something.

It is the responsibility of the thoughtful event planner to first work with the leadership team — not the company’s event team — to ask the leader, what is the purpose of this gathering? There are many thoughtful planners who want to make a difference but struggle with the problem of getting in front of the people who are at the highest levels of an organization.

I wrote this book because I think gathering is a form of leadership — it’s not a form of logistics. And part of this is changing the culture in our companies and in our workplaces that move our assumptions from our gatherings being centered around things to remembering that gathering is actually a form of group leadership around people. I think that gathering is a leadership capability and one that needs to be developed in people. This may not be good news for event planners, but maybe there’s a logistics department. But I think if we change the culture of gathering, this begins to be something that is on each CMO’s resume, on the CEO’s resume, on the engineer’s resume, because all of these people are hosting meetings, are part of product launches. … And you begin to change the culture of how we spend our time together when it’s not just one group of people that think of themselves as having this as their role.

To answer your question specifically from the event-planner perspective, make sure no matter what, even if the client is trying to get into logistics, the first question [is]: What is the purpose of this event? What is your desired outcome? What is it you want people to feel when they walk away from this? Who is this for? Always, always, always … don’t skip the purpose. Lead through your questions.

Technologies, including artificial intelligence, are remaking jobs and industries. What advice do you have for an event planner about remaining relevant?

To not skip over purpose. Assessing somebody’s actual purpose is actually a complicated human problem. We don’t always know our purposes. If there are multiple purposes, we’re not sure which one to choose first. Right? It’s human judgment. It’s discernment. It’s values. It’s emotions. It’s complicated feelings. It’s politics.

Whereas logistics, some could be outsourced, whether it’s by being automated or whether it’s just done better by a larger company that can operate on scale. And so I would say to the event planners, your purpose, more and more, is going to be helping lead leaders, hosts, and decision makers to draw lines in the sand — to figure out, what is this event for, who is this event for, and who is it not for, and to remind them that gatherings are actually a form of transformative leadership.

To learn more about:

- Priya Parker, visit priyaparker.com

- The Feast, visit feastongood.com

- CreativeMornings, visit creativemornings.com